How climate change is impacting the future of our cup of coffee

No matter our position on climate change, we all share the same cup of coffee that we enjoy so much when we wake up, and that gives us that shot of energy when we need it to. Coffee consumption is part of many daily routines, while for the biggest fans it is a real passion rich in experience and complexity. However, our way of living and the pressure we put on the climate are having a knock-on effect on coffee production.

While we are walking through our favourite retail store or coffee shop, we naturally jump to the conclusion that coffee production is easy, fast, diverse and quite resilient due to the wide range of products available. Brazil, Colombia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda…the variety of coffee production must be great, right? Well, not quite. In reality, even though coffee grows in more than seventy countries, the coffee in our cup only comes from two species: Arabica (61.6%) and Robusta (38.4%) that together account for 99% of the world’s total coffee production. On top of the drastically low bio-diversity level, coffee production requires specific environmental conditions to survive and a perfect set-up to thrive. For example, the Robusta coffee grows in lowland Equatorial Africa, particularly in the Congo River Basin and the Lake Victoria forests. It requires abundant and consistent rainfall (around 2000 mm per year) at an altitude of up to 800 metres above sea level. The plants need a temperature between 22°C and 30°C to grow and are highly sensitive to temperatures above or below that range.

A recent study, which aimed at analysing the impact of climate change on coffee production areas, points out the sensibility of coffee production to climate change. The study forecast a 50% reduction in area suitable for coffee production by 2050, with significant losses in the most favourable regions. The increase in temperature, the rain’s irregularity, and the high variability between seasons threaten the availability and quality of our beloved coffee. Beyond the comfort of our cup of coffee, a harsh invisible reality is hitting coffee farmers’ livelihoods and communities that strive to maintain profitability in a constantly changing environment.

The outstanding level of interdependencies between the environmental, economic and social spheres makes analysing the climatic causes and their effects on the coffee value chain challenging and complex. A logical framework around global climate change, its knock-on effect, economic pressure, and social tension can help us understand the coffee value chain’s current situation and possibly leverage solutions to mitigate present and future issues.

The high number of variables required to provide a suitable environment for coffee growth makes coffee production highly sensitive to climate change. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) forecasts an increase in temperature between 1.1°C and 5.4°C by 2100 [1]. Such an increase in temperature implies a shift in the geographic location of lands suitable for coffee plantations. In reaction, producers increase their plantation’s altitude to find the ideal range of meteorological conditions, shrinking the total areas available for a coffee plant to thrive and increasing deforestation. On top of warmer temperatures, climate change induces a shift in global weather patterns with an already observed increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme events such as drought or flooding, which favour the proliferation of pests and diseases. All those elements coupled with the growing unpredictability of climate change create a decrease in yield and quality [2].

The decrease in land available for coffee production is a knock-on environmental effect of the previously mentioned climate changes. As pointed out by the Specialty Coffee Association in its Coffee Production Costs and Farm Profitability strategic literature review[3], as higher and cooler grounds are needed to reach profitability and meet market demand, two phenomena can be observed: intensification of land use and the shift in production location. On the one hand, the intensification of land use directly responds to short-term changes with the extensive use of low-cost fertiliser to increase yield, and pesticides to fight pest and disease proliferation. Ultimately, the intensity of land use and the overuse of chemical products could lead to the soil’s degradation[4], which in the long run could lead to a further decrease in yield and quality. On the other hand, the shift in location for coffee production leads to the exploitation of previously unused land. Such a transition accompanied by the low level of diversity of coffee seeds could, on top of bringing deforestation to those new areas, generate a drastic decrease in biodiversity.

Global climatic changes and their environmental knock-on effects threaten coffee farmers’ profitability, which accounts for 70% of worldwide coffee production[5], in terms of revenue and cost. The decrease in yield and quality directly impacts coffee producers’ revenue by decreasing their sales volume and bargaining power against buyers who are also increasingly struggling to maintain profitability[6]. At the same time, two dynamics are affecting the cost structure of small producers. Firstly, to maintain profitability in the short-term, farmers tend to increase their production process input. Those input costs mainly represent labour, fertiliser, pesticides, or diversification through agricultural practices to maintain yield, such as planting banana trees to create shade and therefore cooler temperatures for the coffee beans. Secondly, the area suitable for coffee plantation moves, generating the need for new production zones, which in turn demands investment in land and seed. Knowing that a coffee tree needs on average five years to produce fruits and that the ground suitable for coffee growth is uncertain in the mid-term to long-term, such an investment bears a risk that not all producers are ready nor able to take. On top of those two dynamics, a study carried out by the Specialty Coffee Association[7] shows that the automatic response to seek an increase in yield to cover the loss in sales is not a viable long-term strategy. In fact, the quantitative study outlines that the marginal revenue of an increase in output is lower than the marginal cost, at least in the short-term. In other words, when a farmer increases their yield by one unit, the extra revenue from it is lower than the additional cost to generate it. That relationship is mainly due to the fact that increasing the quantity requires considerable amounts of investments in land, labour, fertilisers and pesticides, which, in the short-term, are more significant than the possible revenue. That finding outlines the tremendous economic risk generated by the high investment cost for an increase in production without the guarantee of a future return on investment.

Global climate changes, environmental knock-on effects and economic pressure are spilling over into the social structure[8]. Firstly, the economic pressure on farm owners due to the decrease in income caused by the falling level of yield and quality and the shortage of resources to invest is leading to an increase in illegal crops and regional insecurity[9]. Without an income to sustain a living, coffee producers might be incentivised to produce on land they do not own or to cease their business activity altogether, leading to an increase in insecurity in those regions. Secondly, we can observe the new generation, as time passes, turning away from coffee production, leaving both a shortage of labour and an ageing population less resilient to face those new challenges. Ultimately, climate issues are disrupting production patterns, which have been taught and passed on for generations. Such a drastic change coupled with the inability to predict the future climatic impact and adapt production processes in time slowly leads to the loss of the local production know-how.

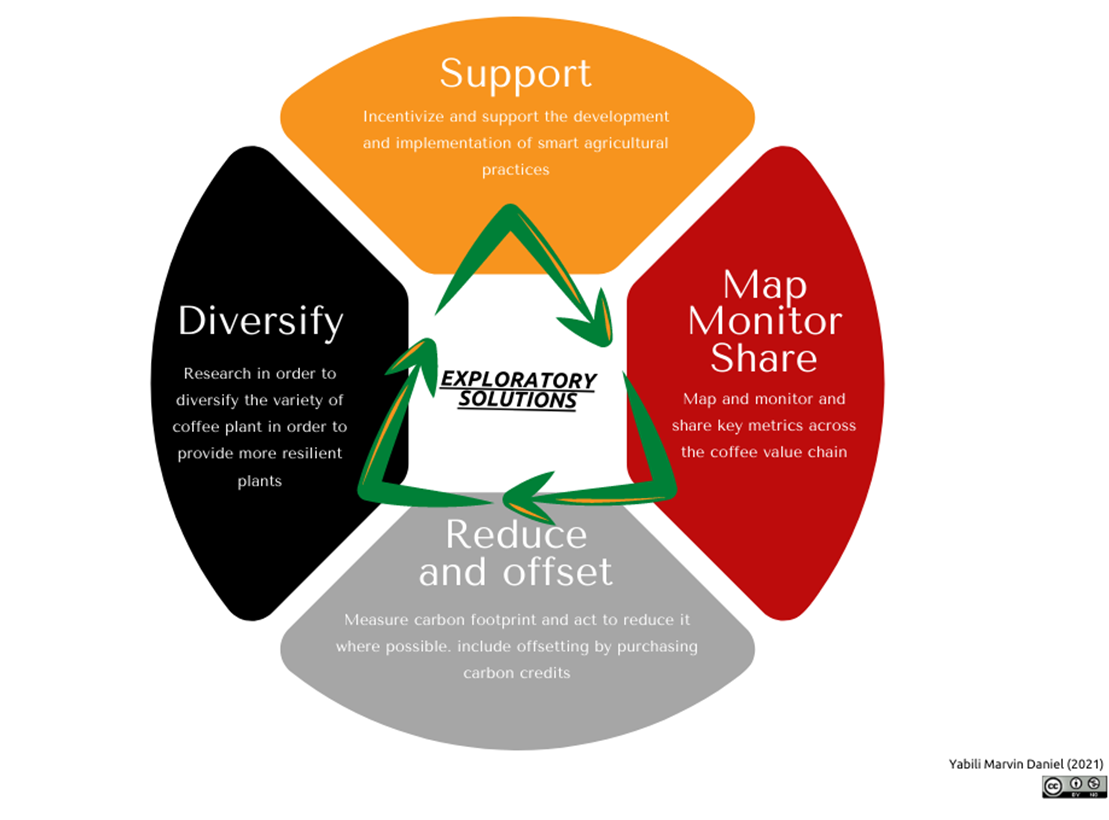

Climate change is, unfortunately, an irreversible process in the short-term. If we want to keep our lovely cup of coffee, we must respond to it with bold initiatives that could at the same time reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt coffee production to the current challenges. Such plans require the implication, flexibility and innovation of all the coffee value chain actors. The value chain’s resilience does not rely only upon the farmer’s ability to deal with their day-to-day challenges. However, on real 360-degree adaptation strategies locally, nationally and internationally among all coffee stakeholders at different stages of the value chain to provide insight, train, advocate and finance the correct response to the present crisis. Four possible solutions can prevent us from having to give up our cup of coffee.

The more immediate solution to climate impact mitigation is to support the ‘Climate Smart Agriculture’[1] (CSA) best practices in terms of techniques such as soil fertility, agroforestry or the protection of watersheds. Such support would ideally help farmers gain access to knowledge, inputs and markets. The goal of supporting CSA projects is to assess the climate change exposure of coffee systems and develop appropriate farmers’ practices to increase the community’s resilience. Such procedures could be leveraged to create and implement regional strategies while promoting access to the investment needed to maintain a decent income and a sufficient supply level. Agroforestry, for example, a land-use management system in which trees or shrubs are grown among crops, is one of the possible solutions that could mitigate the scope of the four areas of impact mentioned previously[2]. Effectively, as climate change impacts producers, agroforestry delivers a proven path to secure biodiversity, soil and plant growth to a certain extent. Most importantly, it keeps land suitable for production by providing shade and, therefore, cooler temperatures. For the coffee plantations, adding banana plants has been an efficient solution for many producers by first keeping the land suitable for coffee growing and secondly by diversifying the sources of revenue. Supporting projects like CSA by identifying the synergies between coffee plants and other trees and financing the transition could help build more resilient coffee production. Knowledge sharing and joint action among local and global stakeholders need to be efficient to meet adequate market quantity-quality requirements.

Leveraging the power of shared knowledge is an asset that could only be used after understanding how climate change impacts each producer group, how they adapt, and how the political and social landscape in the locality influences their adaptation strategies. Currently, the lack of research and transparency on the subject prevents the inception of global action across the value chain. Therefore, it is essential to map out the current situation and the different stakeholders impacted directly and indirectly by the changes. Considering the variety of stakeholder goals, a set of metrics should be defined to monitor and report on the economic, environmental and social issues throughout the value chain. The bottom-up aggregation of information and the common sharing of knowledge could, as a consequence, allow the different stakeholders to conduct valuable strategies that leverage synergies thanks to models such as the doughnut economy by Kate Raworth[3].

On top of the global monitoring and evaluation of the coffee value chain, individual actions should be taken to mitigate climate change at each step. Two approaches must be taken to achieve this goal: supporting activities that help farmers adapt to climate change, and decreasing carbon emissions that accelerate that change. Therefore, companies at the end of the value chain could lead by example by monitoring, pricing and reducing their carbon emissions with measures to decrease waste and invest in eco-friendlier activities. At this stage, it is essential to note that individual actions do not bring sustainable changes throughout the value chain. Leveraging carbon pricing[4] could be a path to align the low and high end of the value chain’s interests. In fact, local cooperatives can be certified through the Gold Standard as carbon offsets by planting trees in areas left behind due to their inability to produce coffee beans . Having such a certification could mitigate the effects of climate change and make coffee plantations less susceptible to the risk of critical climatic events such as flooding, landslides, pests or diseases. The revenue from carbon credit could help coffee farmers with technical and labour assistance while enabling traders and roasters to invest in the communities’ longevity where they buy coffee and account for their carbon emissions.

Ultimately, diversifying the variety of coffee plants could help increase the resilience of coffee farms. In practice, coffee farmers usually use few types of coffee. Such a low variety of coffee plants could result from low-level national investment in coffee research, the lack of coffee seed diversity knowledge or the tradition among countries that do not share genetic material[5]. With an input cost critical for profitability, having resilient coffee plants is vital for the coffee value chain’s survival. The international Multilocation Variety Trial[6] or IMLVT is an excellent example of what could be done to improve that aspect. The IMLVT works on the potential for existing varieties to address current and future climatic challenges by creating mechanisms for the evolution of plant varieties and sharing across countries. Knowing the coffee farmers’ input cost, introducing the best performing varieties as soon as possible at a reasonable price could increase supply and quality without a drastic increase in cost.

Climatic changes, environmental knock-on effects, economic pressures and social tensions push the industry’s low-end up against a wall that requires bold actions to break through. Therefore, we should consider innovative ways of dealing with that complex problem by implementing solutions supporting, informing, mitigating and reinforcing the industry. On the one hand, we can observe an increase in consideration for such solutions to face the future economic, environmental and social consequences of a previously non-resilient value chain. The beauty of having a rich and complex cup of coffee is a luxury that is threatened by the structural fragility of the coffee value chain. However, the joint action of different value chain stakeholders could lead to a bright and sustainable future for all.

Text: YABILI MARVIN, Daniel